ARCAS (URSA MINOR)

2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55.25 inches

Imagining Thomas Jefferson if he had acknowledged his children with Sally Hemings, a woman he enslaved.

Detail of ARCAS (URSA MINOR)

2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55.25 inches

Detail of ARCAS (URSA MINOR)

2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55.25 inches

Detail of ARCAS (URSA MINOR)

2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55.25 inches

The sleeping bear refers to a gift of two grizzly bear cubs to Thomas Jefferson from Captain Zebulon Pike who acquired them in the southern region of the great Continental Divide where he wrote they “were "considered by the natives of that country as the most ferocious animals of the continent."

QUEEN ON HER OWN COLOR

2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55 inches

Queen on Her Own Color depicts Thomas Jefferson with Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman who became Thomas Jefferson’s property as a girl, through his wife’s inheritance.

Contextualizing texts from the Monticello site follow:

Unlike countless enslaved women, Sally Hemings was able to negotiate with her owner. In Paris, where she was free, the 16-year-old agreed to return to enslavement at Monticello in exchange for “extraordinary privileges” for herself and freedom for her unborn children. Over the next 32 years Hemings raised four children—Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston—and prepared them for their eventual emancipation. She did not negotiate for, or ever receive, legal freedom in Virginia.

…

[Sally Hemings’ son], Madison Hemings recounted that his mother “became Mr. Jefferson’s concubine” in France. When Jefferson prepared to return to America, Hemings said his mother refused to come back, and only did so upon negotiating “extraordinary privileges” for herself and freedom for her future children. He also noted that she was pregnant when she arrived in Virginia, and that the child “lived but a short time.” No other record of that child has been found.

The Monticello site offers no proving account of Hemings’ negotiation for her personal freedom, or her reason for trusting Jefferson to keep his promise. Pregnant at the age of 16, we wonder what kind of choice she really had. She returned from Paris, where she was free, to Virginia as an enslaved household servant and lady’s maid. She bore at least six children fathered by Thomas Jefferson. Decades after the Paris negotiation, her four surviving children were freed—two daughters in the early 1820’s and her two sons only after Jefferson died in 1826. Never legally emancipated, Sally Heming was unofficially freed—or “given her time”—by Jefferson’s daughter Martha after his death.

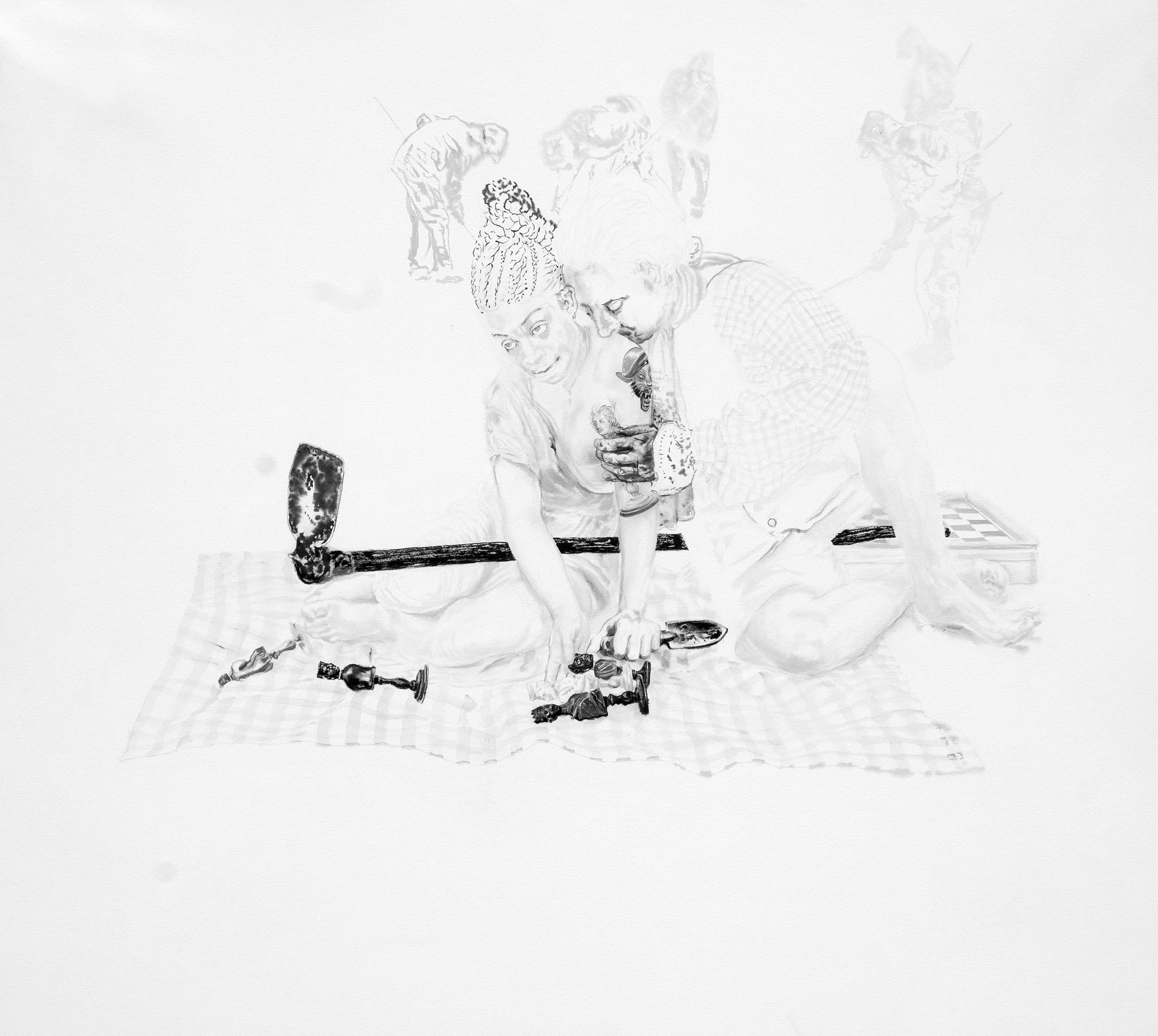

In the game of chess, “The King and Queen, as the most significant pieces, stand in the middle of the chessboard. Chess rules dictate “queen on color,” meaning the White Queen goes on a light square and the Black Queen on a dark square, supposedly because the King is a gentleman and invites the Queen to stand on her own color.

These rules suggest a patronizing chivalry toward both an official and intimate partner. In the drawing, Sally Hemings and Jefferson sit on a checked cloth. Their ‘leisure,’ with or without consent, is staged against a backdrop of enslaved field laborers. Jefferson makes advances on her while holding a white queen. Hemings’ black pieces are toppled but her hoe and trowel both have blades— aspirational tools for a cannibalized ‘love.’

Detail of QUEEN ON HER OWN COLOR

(Checks) 2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55 inches

Detail of QUEEN ON HER OWN COLOR

(A favored trowel) 2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55 inches

Detail of QUEEN ON HER OWN COLOR

(Fairest of them all) 2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55 inches

Detail of QUEEN ON HER OWN COLOR

(On whose shoulders we stand) 2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 55 inches

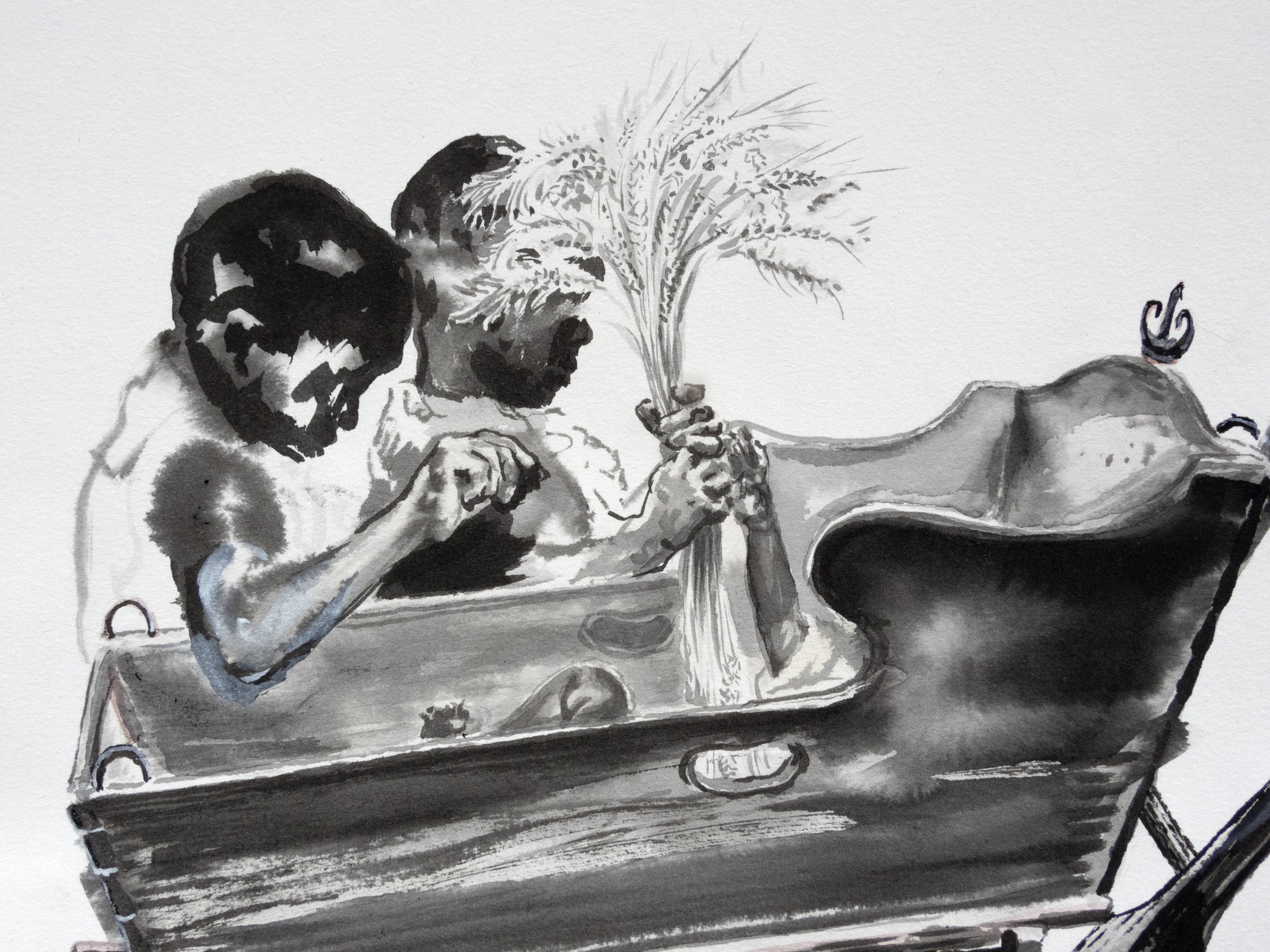

WAITING FOR ISAAC AND JOHN

2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 54.5 inches

To survey his estate, an aging Thomas Jefferson needed to be ferried around in a wheelbarrow. Isaac Jefferson and John Hemings were both enslaved at Monticello.

Detail of WAITING FOR ISAAC AND JOHN

(Cow lick) 2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 54.5 inches

Detail of WAITING FOR ISAAC AND JOHN

(Roman Garb) 2021, Ink on paper, 49.5 x 54.5 inches

Jefferson at Half Rations, 2021

Ink on paper, 50 x 55.75 inches

The economic implications of slavery are infinite. The enslaved were a financial bonanza for Jefferson, a perpetual human dividend at compound interest.

Jefferson wrote, “I allow nothing for losses by death, but, on the contrary, shall presently take 4% credit per annum, for their increase over and above keeping up their own numbers.”

Jefferson is portrayed here gaunt from the half rations that were proscribed for the sick and elderly for underproducing. He bears a smoldering dependent.

Detail of JEFFERSON AT HALF RATIONS 2021

A smoldering descendent

CRADLE PLOW: RUSTLE 2022

Ink on paper, 24 x 38 inches

Based on Thomas Jefferson’s drawing of a plow and calculations of capital.

“But still viewing slave selling as a last resort, Jefferson turned to slave leasing and mortgaging for income. Jefferson’s ability to hire slaves out and use them as collateral to secure loans was based on the increased value of slave bodies and the “natural increase” of the slave population. Unlike in the Caribbean, this increase allowed Virginia planters to satisfy the demand for slave labor without having to import slaves from Africa. Jefferson himself encouraged the reproduction of his slave population. In particular, Jefferson understood that female slaves—and their future children—represented the best way to increase the value of his holdings, what he called “capital.” “I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm,” Jefferson wrote in 1820. “What she produces is an addition to the capital,” while a male slave’s “labors disappear in mere consumption.”9 In 1819, worried by a spike in infant mortality at Poplar Forest, Jefferson believed that it was for “moral as well as interested considerations” that overseers should preserve slaves’ lives, not for “their labor, but their increase.”10 As Jefferson’s friend and neighbor John Hartwell Cocke observed, Virginia slaveowners increasing believed that their “profits consists in the increased number & value of their slaves,” rather than in the crops that their bondspeople produced.”11

From Monticello.org

Detail from CRADLE PLOW: RUSTLE 2022

Ink on paper, 24 x 38 inches

CRADLE PLOW: SPELL 2022

Ink on paper, 24 x 38 inches

Based on Thomas Jefferson’s drawing of a plow and calculations of capital.

“By 1794, Jefferson had put his plans into action at Monticello. He had a plow fitted with a wooden moldboard of his design and later reported to Sir John Sinclair that "an experience of 5. years has enabled me to say it answers in practice to what it promises in theory." In addition to offering the least resistance as it was pulled through the soil, Jefferson's moldboard had a further advantage: "[I]t may be made by the coarsest workman, by a process so exact, that it's form shall never be varied a single hair's breadth." Ease of duplication was thus another measure of the usefulness of his design.”[4]

4. Jefferson to Sinclair, March 23, 1798, in PTJ, 30:201-05. Transcription available at Founders Online.

Detail from CRADLE PLOW: SPELL 2022

Ink on paper, 24 x 38 inches